John Hoyland showed in London's Situation exhibition, which kickstarted the 60s art scene, and his career took off from there.

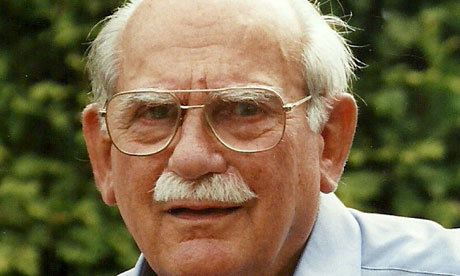

A painter and printmaker of prodigious creative energy and imagination, John Hoyland, who has died aged 76 of complications following heart surgery in 2008, was widely recognised as one of the greatest abstract artists of his time. From the beginning of his career, he unwaveringly championed the centrality of abstraction to the living history of modernist art. "Non-figurative imagery possessed for me," he wrote, "the potential for the most advanced depth of feeling and meaning."

For Hoyland, it was necessary for paintings to be self-sufficient machines, constructed to convey a powerful charge of visual, mental and emotional energy without recourse to any historically established figurative imagery. The expressive force of his paintings derives from the intensity and conviction of their engagement with colour, scale and abstract form, rather than with any direct expression of personal feeling. Hoyland understood the force of Braque's wonderful maxim: "Sensation, revelation!"

Hoyland was born in Sheffield to a working-class family. He was educated from the age of 11 in the junior art department at Sheffield College of Art, progressing to the senior school four years later. It was there that he met his first great friend in art, Brian Fielding, and began his passionate critical-creative engagement with painting.

The work in his finals show at the Royal Academy Schools, London, in 1960, was ordered off the walls by the then president of the Royal Academy, although Hoyland was still awarded his diploma. Within months, he was exhibiting with some of the best British artists of the day in Situation, a show of "large abstract paintings" organised by the artists themselves with a little help from the critic Lawrence Alloway. Situation kickstarted the 60s art scene, and London quickly became one of the most exciting art capitals in the world.

Hoyland was the youngest artist in the show, and his career followed a spectacular trajectory over the course of the decade. After showing in the follow-up exhibition, New London Situation, in 1961, he was taken on by Marlborough, at that time the most prestigious commercial gallery in London. When a critic described his paintings as "exquisite and refined", Hoyland was shocked: "Painting should be a seismograph of the person, and if I'm being 'exquisite', I'm being false. That's why I ditched all that optical hard-edge painting." It was by no means the last time Hoyland would attain a mastery of means, only to change direction deliberately and reinvent his manner and style.

In March 1964, Hoyland was featured in Bryan Robertson's New Generation showcase of young painters at Whitechapel Art Gallery, joining a brilliant galaxy of rising stars including Patrick Caulfield (who became a lifelong friend), David Hockney, Paul Huxley, Alan Jones and Bridget Riley. Not long after, he embarked on an astonishing series of huge acrylic canvases of high-key deep greens, reds, violets and oranges deployed in radiant fields, stark blocks and shimmering columns of ultra-vibrant colour. It was an achievement in scale and energy, sharpness of definition, originality and expressive power unmatched by any of his contemporaries, and unparalleled in modern British art. Visiting the studio in late 1965, Robertson immediately proposed a full-scale exhibition at the Whitechapel.

His one-man exhibition at that gallery in the spring of 1967 was a defining moment in the history of British abstract painting. It consolidated Hoyland's reputation, and established him without question as one of the two or three best abstract painters of his generation anywhere in the world.

Hoyland went to live and work in the United States in the late 1960s, and he was welcomed into the company of New York artists and critics including Clement Greenberg, Robert Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler, Barnett Newman and Kenneth Noland. Although he counted the younger "cooler" painters such as Noland, Larry Poons and Jules Olitski among his friends there, it was always the brave and visionary older generation painters with whom he felt most sympathy.

Newman especially struck a deep chord: "The image we produce," Newman had written, "is the self-evident one of revelation, real and concrete, that can be understood by anyone who will look at it without the nostalgic glasses of history."

Hoyland never felt particularly happy in the competitive hothouse of east coast painting. Encountering in a New York gallery the work of Hans Hofmann and recognising its European roots was a crucial epiphany. Acknowledging that he belonged essentially within the tradition of British and northern European colouristic expressionism, in 1973 Hoyland returned to England. Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, Emil Nolde and Nicolas de Staël had all been deeply admired by Hoyland from early in his artistic life. His painting from this time until the mid-1980s was to be characterised by high colour, architectonic structures loosely based in geometric forms, and a richly textured, painterly surface.

For a talk at the Tate in the 80s, Hoyland wrote a wonderfully undiscriminating and inclusive list of the subjects, experiences and objects that fired his imagination: "Shields, masks, tools, artefacts, mirrors, Avebury Circle, swimming underwater, snorkelling, views from planes, volcanoes, mountains, waterfalls, rocks, graffiti, stains, damp walls, cracked pavements, puddles, the cosmos inside the human body, food, drink, being drunk, sex, music, dancing, relentless rhythm, the Caribbean, the tropical light, the northern light, the oceanic light. Primitive art, peasant art, Indian art, Japanese and Chinese art, musical instruments, drums, jazz, the spectacle of sport, the colour of sport, magic realism, Borges, the metaphysical, dawn, sunsets, fish eyes, trees, flowers, seas, atolls. The Book of Imaginary Beings, the Dictionary of Angels, heraldry, North American Indian blankets, Rio de Janeiro, Montego Bay!"

To which might be added: Zen poetry, classical, modern and contemporary painting and sculpture, domestic pottery, driving cars, humming birds, gulls and reptiles, eclipses of the sun and moon. At any time, Hoyland might be reading and absorbing the writings of Miró, the poetry of Frank O'Hara, the novels of Gabriel García Márquez, and Japanese and Chinese poetry. All of these things fed a voracious appetite for sensory, intellectual and emotional experience in a life of sharp sight and heightened receptivity, free of preconception and cliche.

Some critics found the uninhibited exuberance of Hoyland's later painting, its superabundance of effects and its technical extremism, overwhelming. But those who loved this work were exhilarated by its spectacular diversity of visual effect, and by its impulse towards fantasy released by a heroic ambition that took him again and again to the extreme of what painting might achieve. Hoyland was always a maker of evocative images, with a disposition to the grandly visionary-poetic which has been rare in English painting since that of his greatest heroes, Turner and Constable.

Hoyland was a critically generous and able advocate of British abstract art (he counted Anthony Caro among his closest friends, and acknowledged the great sculptor's enduring influence on him). He was a constant supporter of succeeding generations of younger abstract artists, who found in him an eloquent mentor and friend. In 1979, he selected the Hayward Annual, an exhibition that remains a landmark in the history of British abstract painting. In 1988, he curated an important exhibition at the Tate Gallery of late paintings by Hofmann. He was elected Royal Academician in 1991. In 2006, Tate St Ives held the exhibition John Hoyland: The Trajectory of a Fallen Angel, bringing together paintings from 1966 to 2003.

Hoyland was a man of acerbic wit, and a wickedly cruel mimic, but behind a carefully crafted persona there was enormous generosity of spirit and true kindness. A lover of pubs and restaurants, he was a man without side, utterly un-snobbish, and ever aware of his working-class beginnings. He was an inveterate traveller, visiting South America (with Caro), Australia (with Caulfield), and latterly Spain, Italy, Jamaica and Bali with his longterm companion, Beverley Heath, whom he married with great joy in 2008. Wherever he went, he relentlessly gathered ideas and impressions, in photographs and sketchbooks, as sources for imagery. Nothing was lost and nowhere was alien to this most complete of artists.

He is survived by Beverley; his son, Jeremy, from his first marriage, to Airi; and his mother, Kathleen.

• John Hoyland, painter, printmaker and teacher, born 12 October 1934; died 31 July 2011