Lucian Freud with Martin Gayford in 2010.

The original, unnerving, sustained artistic achievement of Lucian Freud, who has died aged 88, had at its heart a wilful, restless personality, fired by his intelligence and attentiveness and his suspicion of method, never wanting to risk doing the same thing twice. The sexually loaded, penetrating gaze was part of his weaponry, but his art addressed the lives of individuals, whether life models or royalty, with delicacy and disturbing corporeality.

Freud had a reputation for pushing subjects to an extreme. But unlike the American painters to emerge in the 1950s, his approach was in the western tradition of working from life and brought about with painstaking slowness, rather than unleashed virtuosity. Photographs taken in the studio by his assistant, model and good friend, the painter David Dawson, show Freud working from a roughly sketched charcoal form, the paint slowly spreading outwards from the head. Some canvases were extended, others abandoned while still a fragment.

Portraits of his maturity drew comparisons with equally shocking works by Courbet, Titian and Picasso, the feelings exposed registering as both brash and profound. The recorded stages of Ria, Naked Portrait 2006–07, his last large female nude, indicate the suspenseful build-up of pigment on her toe and the radiator; heavy incretions represent her curls and flushed face.

By 1987, the critic Robert Hughes nominated Freud as the greatest living realist painter, and after the death of Francis Bacon five years later, the sobriquet could be taken as a commendation, or it could imply an honour fit for an anachronistic "figurative" artist working in London. Art critics since Freud's first shows in the 1940s have had difficulties situating his achievement; the common solution has been to apply adjectives to the painted subjects in a way that reflects little more than personal taste, the writers telling readers whether the person portrayed was bored or intimidated, scrawny or obese, the paint slathered, crumbly or miraculously plastic.

Others, however, eschew this moralising tone and are prepared to be startled. Aidan Dunne, for example, reviewing the exhibition in Dublin in 2007, recognised how a single blonde model, "unmistakably" herself, in 1966 led Freud to push "the bounds of decorum in terms of mainstream depictions of the human body considered not as a generic type but as, to use his own term, a "naked portrait". Freud painted three versions of this fine-boned young woman on a cream cover, seen from above, each one a masterpiece. Her pictorial availability seems to some degree predicated on the artist's subtle way of incorporating in his paint strokes the upheavals and new perils that would enliven traditional gender relationships.

Freud was born in Berlin, to Ernst Freud, an architect and Sigmund's youngest son, and Lucie Brasch. The family lived near the Tiergarten, with summers spent on the estate of Freud's maternal grandfather, a grain merchant, or at their summer house on the Baltic island of Hiddensee.

Realising the Nazi threat to Jews, his parents, Lucian and his brothers – Stephen and Clement – moved to England in the summer of 1933. At Dartington Hall, Devon, and then Bryanston, Dorset, the boy was preoccupied by horses and art rather than the classroom. He enrolled at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, London, in January 1939 but found the laid-back atmosphere repellent and rarely attended classes.

From 1939 to 1942 he spent periods at the unstructured school founded by Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines in East Anglia, first in Dedham, Essex, and then at Hadleigh, Suffolk. Morris proved a sympathetic mentor, one whose confidence and application gave Freud a sense of what it might mean to be an artist. In March 1941 Freud signed on as an ordinary seaman on the armed merchant cruiser SS Baltrover, bound for Nova Scotia. The ship came under attack from air and then by submarine, and on the return journey he went down with tonsillitis.

By the age of 18, the charismatic, talented young man with a famous name had attracted friends such as Stephen Spender and the wealthy collector and patron Peter Watson. Freud began visiting Paris, first in 1946 while on his way to Greece, where he stayed for six months, and again in 1947, with Kitty Garman, niece of his previous girlfriend Lorna Wishart, daughter of Jacob Epstein and the subject of one of the first major paintings, Girl in a Dark Jacket 1947. His connections in Paris extended to people linked to the arts in the 1930s, such as the hostess and collector Marie-Laure de Noailles.

The handful of surviving postcards contain no mention of postwar deprivations as he offers Méraud Guinness Guevara witty accounts of the installation of André Breton's surrealist exhibition in Paris in 1947, designed by Marcel Duchamp and Frederick Kiesler, and thanks for her hospitality in Provence. Freud expresses admiration for the "malevolence" the French showed to foreigners.

On familiar terms with Alberto Giacometti and Balthus, and, to some degree, Picasso, one senses that the young Freud was marked for life by seeing how single-mindedly, and self-critically, these already famous artists pushed forward their art. When he moved in 1943 to Delamere Terrace on the Grand Union canal, the first of five addresses in Paddington, London, several of his Irish working-class neighbours became models, especially the brothers Charlie and Billy. A large picture with a spiky palm tree and a tense, young Eastender, Harry Diamond, comprises a poignant drama about survival, Interior in Paddington 1951.

Paintings of Freud's two wives – Garman (whom he married in 1948 and divorced four years later) and Caroline Blackwood (whom he married in 1953 and divorced in 1957) – and other intimate friends are filled with suspense and pain, apparent in the strands of hair and a hand raised to the cheek as much as the wide eyes. The pearly skin of these subjects becomes more translucent and the detail extra-perfect. In an article written in 1950, the critic and curator David Sylvester questioned the perversity of feeling in Freud's latest portrayals. "It is impossible to say whether this indicates the incipient decline of an art whose talent flowered remarkably early or simply that every new departure implies growing-pains."

By the time of the Venice Biennale in 1954 – Freud shared the British pavilion with Bacon and Ben Nicholson – the question of prodigy versus an ultimately significant artist was being argued regularly. Freud's only involvement with the art colleges came though accepting William Coldstream's invitation to join the new staff at the Slade in 1949 (he made occasional appearances in the studios until 1954).

It became convenient to account for shifts in Freud's work by focusing on his early reliance on drawing and to cite the influence of painters from northern Europe such as Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Albrecht Dürer, or even to suggest a false comparison with the Neue Sachlichkeit painters (active in Germany in the 1920s but unknown to the young Freud) and overlook others as relevant as Paul Cézanne and Chaim Soutine. The significance of the change from sable to hogs' hair brush and flake white to Kremnitz white in the late 1950s was exaggerated. Freud was attracted to Bacon's merciless wit and risk-taking, admiring his impulsive handling of paint, yet curiously it was Bacon who tried repeatedly to fix an image of his younger friend's physical magnetism.

By the end of the 1950s Freud's fraught personal life contributed to a visual restlessness, and he began standing to paint, letting the raked perspective exaggerate the anatomies of his subjects. A greenish-yellow palette and vein-marked skin made the subjects, such as Woman Smiling 1958-59, superficially less attractive; the paintings exhibited at the Marlborough Gallery in London in 1958 and 1963 were harder to sell.

Freud's obsession with gambling on horses and dogs brought on debts and dangerous threats, although many of the most singular paintings are of fleshly men within the racing fraternity. The journalist Jeffrey Bernard, describing Freud's afternoons in the betting shop and evenings with the rich and distinguished (including "Princess Margaret's set"), wrote admiringly: "He has cracked the nut of how to conduct a double life." The artist's slightly leering face and naked shoulders appear between the fronds of a giant Deremensis, Interior with Plant, Reflection Listening 1967–68. A superb, dangerously over-worked, standing self-portrait, Painter Working, Reflection 1993 portrays the ageing artist wearing only unlaced boots, holding a palette and knife (he was left-handed), addressing the viewer like a silent actor; invariably paint applied imaginatively to the planes of walls and floor reads as though a leitmotif for the prevailing mood. Each millimetre, he insisted, had to become essential to the whole.

In the 1980s the bodies of the nudes pressed into the surrounding space, their three-dimensionality and almost modelled impasto describing deeply contoured forms like those within Freud's favourite bronzes by Rodin – Naked Balzac and Iris. Freud spoke of his curiosity about "the insides and undersides of things".

The reserved Bella Freud placed diagonally on a red sofa (1986) is one of the artist's masterpieces. Leigh Bowery and Freud had a mutually sustaining friendship that went on until just before the performance artist succumbed to an Aids-related illness at the end of 1994. Bowery's "wonderfully buoyant bulk was an instrument I felt I could use in my painting"; "yet it's the quality of his mind that makes me want to portray him". In front of Titian's Diana and Actaeon in 2008, he explained: "When something is really convincing, I don't think about how it was done, I think about the effect on me."

Several paintings approach allegory revisited as parody, beginning with Large Interior, W9 1973 (his mother and his lover), and the heavily promoted Large Interior W11 (After Watteau) 1981–83, with its awkward (and memorable) conjunction of five people from the artist's intimate life. Sitters sometimes came separately, as with Evening in the Studio, where the model Sue Tilley sprawls on the floor in the pose of seaside postcards with captions such as "Roll over Betty". The shuttered interior in Freud's house in Notting Hill was recorded in several large paintings, one now in a Dallas museum: a long-time friend, Francis Wyndham, sits reading in the foreground, whippet at his feet, and in the space beyond, a hybrid Jerry Hall/David Dawson nurses her son.

Annabel Mullen was painted with her shaggy-haired dog Rattler and reappears seven years later with a pregnant belly in Expecting the Fourth 2005 (only 10x15cm), and in a larger etching, limbs still like a thoroughbred, as described by one of Freud's favourite authors, Baudelaire: "vainly have time and love sunk their teeth into her".

Freud's exceptional ability to convey tactile information is evident in early drawings, especially those of gorse sprigs, a dead heron and a bearded Christian Bérard in a dressing gown. A similarly heightened, highly poetic, sensibility invades the etchings that began in the 1980s, black whorls and stippled textures fanatically worked, the artist relishing the "element of danger and mystery" that accompanies slipping a heavily worked plate into acid.

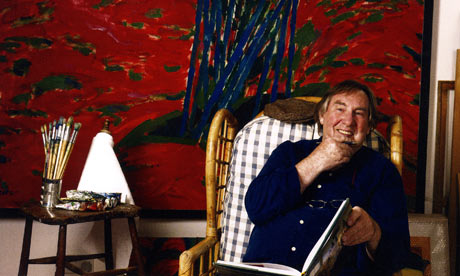

International exposure increased after the 1974 Hayward exhibition, nurtured by Freud's admirers, particularly William Feaver, curator of the Tate retrospective in 2002, and the dealer James Kirkman. The revival of interest in painting that emerged around 1980 led to outstanding British artists being ringfenced with an inappropriate label, the School of London. Freud thought his close friend Frank Auerbach the best British painter of his lifetime. Auerbach understood how no original concept or idiom could be credited with the mesmerising reality of art: "I think of Lucian's attention to his subject. If his concentrated interest were to falter, he would come off the tightrope. He has no safety net of manner."

A retrospective organised by the British Council reached Washington, Paris, London and Berlin in 1987–88, and the "recent work" exhibition created by the Whitechapel Gallery in 1993 drew crowds in New York and Madrid as well as the East End. Freud's representative from 1993, William Acquavella, had a buoyant, unwavering reckoning of the artist's worth – in others words in the league of 20th-century masters. In 2007 the Museum of Modern Art in New York organised an exhibition with great impact, titled The Painter's Etchings, Freud's place in postwar art history admitted through a side-door rather than placed in the canon.

The completion of a single picture turned into a newsworthy event. In 1993 a Daily Mail front-page headline asked: "Is this man the greatest lover in Britain?" A disconcerting recent painting, the artist working while "surprised by a naked admirer", fed readers' curiosity about the octogenarian's love life. The rather sensational Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995) achieved a record auction price for a living artist in May 2008, £17m, by which time Russian oligarchs had joined the wealthy North American collectors who had already replaced upper-class British patrons. The promotion of pictures at auction sometimes gave unfortunate prominence to the failures, notably the truncated picture of a pregnant Kate Moss.

The artist related his acceptance of the Order of the Companions Honour in 1983 and the Order of Merit in 1993 to his family's debt to Britain, the country that allowed them naturalisation in 1939. Freud described the move to England as "linked to my luck. Hitler's attitude to the Jews persuaded my father to bring us to London, the place I prefer in every way to anywhere I've been."

Queen Elizabeth II sat for a small portrait in 2001 which Freud donated to the Royal Collection. He selected the pictures for the important Constable exhibition that opened in Paris in 2002, respecting the artist's "truth-telling. The way he used the undergrowths to suit himself – things being soaked in water and so on – was a way of looking at nature that no one had really done before."

The portraits Freud made of his mother, beginning in 1972 and ending with a drawing from her deathbed in 1989, are a remarkable elegy of ageing and depression. When his children (15 or so were recognised) began leading independent lives, most of them came to sit for him and he was proud of their talents. Bella Freud is a fashion designer and four others are successful writers – Annie Freud, Esther Freud, and Rose and Susie Boyt. Contrary to what has been written about anonymity, the identities of at least 168 sitters have been revealed in various interviews, commentaries and published information.

Thinking about the women who were closest to him for the longest duration, one realises how reticent they preferred to be, particularly Baroness Willoughby d'Eresby and Susanna Chancellor. Any biography of the artist that is written with the claim to analyse character or feelings is doomed.

The list of those he knew and affected would be enormous (and incomplete), the narratives lopsided, with anecdotes and memoirs exaggerating their author's familiarity. Freud's own, sharp recollections are both exciting and skewed. He recently spoke of how it amused him to hold the heads of schoolmates under water, but his occasional violence was countered by a precise, rather Germanic use of language and good manners.

An admitted control freak, who lived alone and liked to use the telephone but not give out his number, Freud kept relationships in separate compartments. He lived with the same aesthetic as that of his work – fine linen, worn leather, superb works of art (and a few cartoons), buddleia and bamboo in the overgrown garden and the residue of paint carried down from the studio. In this setting, he sustained until the end his ability to make portrayals of many of the people and animals who mattered to him (the one still on the easel, Portrait of a Hound), paintings that face-to-face are all-consuming and oddly liberating.

• Lucian Michael Freud, artist, born 8 December 1922; died 20 July 2011