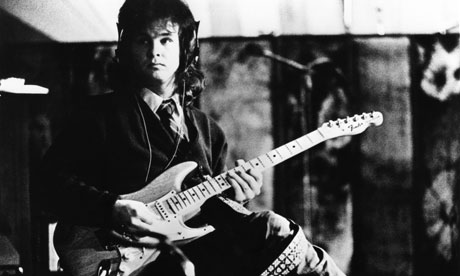

Georgy Girl, with Lynn Redgrave as Georgina and James Mason as her admirer, directed by Silvio Narizzano.

The film and TV director Silvio Narizzano, who has died aged 84, handled several genres throughout his career, including black comedies, period pieces, social dramas, action thrillers and horror movies. But one picture, his swinging London romantic comedy Georgy Girl (1966), stands out from the rest of his eclectic filmography.

Georgy Girl was part of the trend in which British cinema shifted the focus from provincial life and back to the metropolis, celebrating new freedoms and social possibilities. Narizzano, influenced by the French New Wave and his chic contemporaries Richard Lester, John Schlesinger and Tony Richardson, explored such "shocking" subjects as abortion, illegitimacy, adultery and sexual promiscuity with a light touch. The film, which took its cue from the jaunty title song by the Seekers, had superb performances from Lynn Redgrave as the virginal and plain Georgina; Charlotte Rampling as her sexy and amoral flatmate, made pregnant by her charming, laidback boyfriend (Alan Bates); and James Mason as a wealthy businessman who takes more than a fatherly interest in Georgy. The film was nominated for four Oscars, for best actress (Redgrave), supporting actor (Mason), cinematography (Kenneth Higgins) and original song. Narizzano was nominated for a Bafta for best British film and a Golden Bear at the Berlin film festival.

The son of an Italian-American family, Narizzano was born in Montreal and educated at Bishop's University in Quebec. After graduation, he joined the Mountain Playhouse in Montreal. The theatre was run by Joy Thompson, a leading figure in English-language theatre in Quebec and a great influence on Narizzano. He then joined the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, working as an assistant to Norman Jewison, Arthur Hiller and Ted Kotcheff. Soon after co-directing a documentary about Tyrone Guthrie, the artistic director of the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Ontario, Narizzano came to Britain to work in television.

Narizzano's first feature was the Hammer horror film Fanatic.

Narizzano's first feature was the Hammer horror film Fanatic.

Georgy Girl was part of the trend in which British cinema shifted the focus from provincial life and back to the metropolis, celebrating new freedoms and social possibilities. Narizzano, influenced by the French New Wave and his chic contemporaries Richard Lester, John Schlesinger and Tony Richardson, explored such "shocking" subjects as abortion, illegitimacy, adultery and sexual promiscuity with a light touch. The film, which took its cue from the jaunty title song by the Seekers, had superb performances from Lynn Redgrave as the virginal and plain Georgina; Charlotte Rampling as her sexy and amoral flatmate, made pregnant by her charming, laidback boyfriend (Alan Bates); and James Mason as a wealthy businessman who takes more than a fatherly interest in Georgy. The film was nominated for four Oscars, for best actress (Redgrave), supporting actor (Mason), cinematography (Kenneth Higgins) and original song. Narizzano was nominated for a Bafta for best British film and a Golden Bear at the Berlin film festival.

The son of an Italian-American family, Narizzano was born in Montreal and educated at Bishop's University in Quebec. After graduation, he joined the Mountain Playhouse in Montreal. The theatre was run by Joy Thompson, a leading figure in English-language theatre in Quebec and a great influence on Narizzano. He then joined the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, working as an assistant to Norman Jewison, Arthur Hiller and Ted Kotcheff. Soon after co-directing a documentary about Tyrone Guthrie, the artistic director of the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Ontario, Narizzano came to Britain to work in television.

Narizzano's first feature was the Hammer horror film Fanatic.

Narizzano's first feature was the Hammer horror film Fanatic. He rapidly reached the top as a director, gaining plaudits for his work on ITV Television Playhouse (1956-60), a series of Saki tales (1962) and ITV Play of the Week (1956-63), all with superb casts and writers. He directed JB Priestley's anti-nuclear play Doomsday for Dyson (1958); an episode of the BBC series On Trial, starring Micheál MacLiammóir as Oscar Wilde (1960); and 24 Hours in a Woman's Life (1961), starring Ingrid Bergman and adapted by John Mortimer from Stefan Zweig's novel.

Narizzano's feature debut was Fanatic (1965), a Hammer horror film notable for being Tallulah Bankhead's last movie (and her first in 20 years). She plays a crazed religious fanatic who keeps her dead son's fiancee (Stefanie Powers) prisoner, hoping to "cleanse" and then kill her so that she can marry the dead son in heaven. Narizzano managed to coax a venomous performance out of Bankhead, who was intoxicated throughout the shoot. After being shown the film with a small audience of her friends, Bankhead, who is seen in many harsh, unflattering close-ups, announced: "Darlings, I must apologise for looking older than God's wet nurse."

The triumph of Georgy Girl was followed by Blue (1968), a plodding western starring Terence Stamp, which opened to withering reviews but, surprisingly, remained Narizzano's favourite film. Loot (1970), a pointless reworking of Joe Orton's mordant play by the comedy TV writers Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, and directed at a rapid pace, was only marginally better received.

Narizzano was more at ease with Why Shoot the Teacher? (1977), a feelgood adaptation of a novel set in Saskatchewan in the mid-1930s. Then it was back to British television with William Inge's Come Back, Little Sheba (1977), fluidly directed on an elaborate studio set, starring Laurence Olivier and Joanne Woodward. In contrast, Staying On (1980), Julian Mitchell's adaptation of Paul Scott's novel, was shot for Granada Television in Simla, India, with Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson.

From the mid-60s, Narizzano lived with his longtime companion, the writer Win Wells, in Mojácar in Andalusia, Spain, as well as keeping a house in London. Wells co-wrote the screenplay of Narizzano's Bloodbath (1979), a weird straight-to-video horror movie, shot in Mojácar, starring Dennis Hopper as the leader of a group of degenerate Americans terrorised by locals for their indulgence in drugs and sex.

After directing a Miss Marple mystery, The Body in the Library (1984), for the BBC, Narizzano's work began to tail off. Since his 30s, he had suffered from bouts of depression which became more serious and prolonged after the death of Wells in 1983. He found some comfort at a Buddhist retreat in Chislehurst, south-east London, and later through a Bible study group in Greenwich, where he lived a semi-reclusive life. He is survived by two sisters and a brother.

• Silvio Narizzano, film and television director, born 8 February 1927; died 26 July 2011

Narizzano's feature debut was Fanatic (1965), a Hammer horror film notable for being Tallulah Bankhead's last movie (and her first in 20 years). She plays a crazed religious fanatic who keeps her dead son's fiancee (Stefanie Powers) prisoner, hoping to "cleanse" and then kill her so that she can marry the dead son in heaven. Narizzano managed to coax a venomous performance out of Bankhead, who was intoxicated throughout the shoot. After being shown the film with a small audience of her friends, Bankhead, who is seen in many harsh, unflattering close-ups, announced: "Darlings, I must apologise for looking older than God's wet nurse."

The triumph of Georgy Girl was followed by Blue (1968), a plodding western starring Terence Stamp, which opened to withering reviews but, surprisingly, remained Narizzano's favourite film. Loot (1970), a pointless reworking of Joe Orton's mordant play by the comedy TV writers Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, and directed at a rapid pace, was only marginally better received.

Narizzano was more at ease with Why Shoot the Teacher? (1977), a feelgood adaptation of a novel set in Saskatchewan in the mid-1930s. Then it was back to British television with William Inge's Come Back, Little Sheba (1977), fluidly directed on an elaborate studio set, starring Laurence Olivier and Joanne Woodward. In contrast, Staying On (1980), Julian Mitchell's adaptation of Paul Scott's novel, was shot for Granada Television in Simla, India, with Trevor Howard and Celia Johnson.

From the mid-60s, Narizzano lived with his longtime companion, the writer Win Wells, in Mojácar in Andalusia, Spain, as well as keeping a house in London. Wells co-wrote the screenplay of Narizzano's Bloodbath (1979), a weird straight-to-video horror movie, shot in Mojácar, starring Dennis Hopper as the leader of a group of degenerate Americans terrorised by locals for their indulgence in drugs and sex.

After directing a Miss Marple mystery, The Body in the Library (1984), for the BBC, Narizzano's work began to tail off. Since his 30s, he had suffered from bouts of depression which became more serious and prolonged after the death of Wells in 1983. He found some comfort at a Buddhist retreat in Chislehurst, south-east London, and later through a Bible study group in Greenwich, where he lived a semi-reclusive life. He is survived by two sisters and a brother.

• Silvio Narizzano, film and television director, born 8 February 1927; died 26 July 2011