Harriet Andersson and Lars Ekborg in Summer With Monika, photographed by Gunnar Fischer.

The Swedish cinematographer Gunnar Fischer, who has died aged 100, could be said to have created the "look" of Ingmar Bergman's films, crystallised in three of the director's masterpieces: Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries (both 1957). From Port of Call (1948) to The Devil's Eye (1960), 12 films in all, Fischer was able to make visible Bergman's visions.

He was born in Ljungby, in southern Sweden. After spending three years in the Swedish navy as a chef, he attended the Royal Academy of Art in Stockholm, where he studied with the celebrated decorative artist Otte Sköld. He had an apprenticeship in cinematography at Svensk Filmindustri (SF), the country's leading production company. His mentor there was the cinematographer Julius Jaenzon, who worked with the two great masters of Swedish silent cinema, Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller. This put Fischer in the direct line of the Scandinavian cinematic tradition of the close relationship between the landscape and climate and the psychology of the characters.

His education was further developed by his work with the great Danish-born Carl Dreyer on Two People (1945), only his third film as director of photography. Despite the fact that this virtual two-hander, mostly set in an apartment, was disowned by Dreyer, Fischer claimed that it was a turning point in his understanding of stark lighting.

He was born in Ljungby, in southern Sweden. After spending three years in the Swedish navy as a chef, he attended the Royal Academy of Art in Stockholm, where he studied with the celebrated decorative artist Otte Sköld. He had an apprenticeship in cinematography at Svensk Filmindustri (SF), the country's leading production company. His mentor there was the cinematographer Julius Jaenzon, who worked with the two great masters of Swedish silent cinema, Victor Sjöström and Mauritz Stiller. This put Fischer in the direct line of the Scandinavian cinematic tradition of the close relationship between the landscape and climate and the psychology of the characters.

His education was further developed by his work with the great Danish-born Carl Dreyer on Two People (1945), only his third film as director of photography. Despite the fact that this virtual two-hander, mostly set in an apartment, was disowned by Dreyer, Fischer claimed that it was a turning point in his understanding of stark lighting.

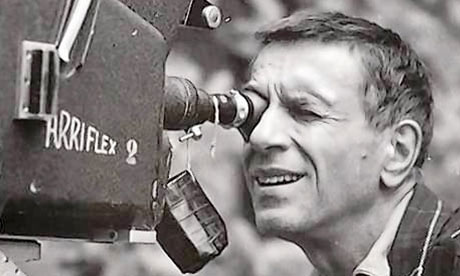

Gunnar Fischer's collaboration with Ingmar Bergman lasted from Port of Call (1948) to The Devil's Eye (1960)

He was unable to practise what he had learned from Dreyer in Port of Call, because it belonged to Bergman's short neorealist period. The picture, about a tormented delinquent girl who turns to a slow-thinking young sailor for love, was largely shot, with Roberto Rossellini in mind, on location in the Gothenburg docks, in a rare attempt by the director to strike an almost documentary tone.

Bergman and Fischer's first mature collaboration was Summer Interlude (1950), in which a prima ballerina looks back on the idyllic summer she spent several years before on an island near Stockholm with the boy she loved. The affair comes to an abrupt and tragic end when he is killed in an accident. Fischer's camera wonderfully captures the limpid Swedish summer in the early, lyrical love scenes, shifting to more shaded lighting for the present.

Even more rapturous was Summer With Monika (1952), where an irresponsible teenage girl spends her holiday on an island with a young clerk, but gets pregnant and leaves him holding the baby. Bergman sees little hope for these adolescents in the winter of their discontent after a summer made glorious by Fischer's camera.

It is no accident that three of Bergman's films have "summer" in the title, and many others were set in that season, the only period of happiness for his characters before the encroachment of autumn and reality, the camera brilliantly recording the transient sun-soaked days. For the charmed comedy of manners Smiles of a Summer Night, which mostly takes place at a country mansion over a weekend during which couples meet, separate and exchange partners, Fischer created sensuous, back-lit twilights.

Sometimes Fischer intentionally overexposed the film to achieve a hallucinatory or dreamlike effect, as in Wild Strawberries. The shift from past to present, from memory to reality to dream, is signified by sharp contrasts in light. "I brought to Bergman a fantasy-like style," he explained. "It wasn't about making the scenes realistic but more theatrical, like a saga." In The Seventh Seal, whose luminous images derived from early church paintings, the change from one moral world to another is conveyed through lighting: a bright natural light indicates characters at peace, while heavy filters and backlighting indicate moral doubt.

In the sequence when the medieval knight plays chess with Death, Fischer used two powerful lights to throw the actors into sharp relief, which made it appear that the sky had two suns. When criticised for this, he responded: "If you can accept the fact that there is a knight sitting on a beach playing chess with Death, you should be able to accept that the sky has two suns."

Fischer and Bergman parted company after The Devil's Eye, which switched between an extremely theatrical Hell and the realism of a pastor's household, when the director failed to persuade the cinematographer to soften his lighting techniques. "I felt privileged collaborating with Bergman," Fischer recalled. "He was never indifferent to photography. He could be upset if he didn't like what he saw. Why our collaboration ended with The Devil's Eye, I don't really know. Realistically it's most likely that he thought Sven Nykvist was a better photographer." Thus began the Bergman-Nykvist era, the stylistic change demonstrating how influential the two cinematographers were to the director's oeuvre.

Away from Bergman, Fischer worked on more mainstream movies. For some of these, he was able to use colour, such as The Pleasure Garden (1961), with a screenplay by Bergman, which was among the four films he made with Alf Kjellin. One of the rare films on which Fischer worked for a non-Swedish director was Anthony Asquith's Two Living, One Dead (1961) a low-key film noir, shot entirely in Sweden with a largely British cast (including Patrick McGoohan and Virginia McKenna) but a mostly Swedish crew. Fischer also experimented with video techniques to record a series of provincial circus acts for Jacques Tati's Parade (1974). After his retirement from the cinema in 1975, Fischer lectured on film lighting.

He is survived by his sons, Jens and Peter, who are both cinematographers. His wife, Gull, the sister of the actor Åke Söderblom, died in 2005 after 67 years of marriage.

• Erling Gunnar Fischer, cinematographer, born 18 November 1910; died 11 June 2011

Bergman and Fischer's first mature collaboration was Summer Interlude (1950), in which a prima ballerina looks back on the idyllic summer she spent several years before on an island near Stockholm with the boy she loved. The affair comes to an abrupt and tragic end when he is killed in an accident. Fischer's camera wonderfully captures the limpid Swedish summer in the early, lyrical love scenes, shifting to more shaded lighting for the present.

Even more rapturous was Summer With Monika (1952), where an irresponsible teenage girl spends her holiday on an island with a young clerk, but gets pregnant and leaves him holding the baby. Bergman sees little hope for these adolescents in the winter of their discontent after a summer made glorious by Fischer's camera.

It is no accident that three of Bergman's films have "summer" in the title, and many others were set in that season, the only period of happiness for his characters before the encroachment of autumn and reality, the camera brilliantly recording the transient sun-soaked days. For the charmed comedy of manners Smiles of a Summer Night, which mostly takes place at a country mansion over a weekend during which couples meet, separate and exchange partners, Fischer created sensuous, back-lit twilights.

Sometimes Fischer intentionally overexposed the film to achieve a hallucinatory or dreamlike effect, as in Wild Strawberries. The shift from past to present, from memory to reality to dream, is signified by sharp contrasts in light. "I brought to Bergman a fantasy-like style," he explained. "It wasn't about making the scenes realistic but more theatrical, like a saga." In The Seventh Seal, whose luminous images derived from early church paintings, the change from one moral world to another is conveyed through lighting: a bright natural light indicates characters at peace, while heavy filters and backlighting indicate moral doubt.

In the sequence when the medieval knight plays chess with Death, Fischer used two powerful lights to throw the actors into sharp relief, which made it appear that the sky had two suns. When criticised for this, he responded: "If you can accept the fact that there is a knight sitting on a beach playing chess with Death, you should be able to accept that the sky has two suns."

Fischer and Bergman parted company after The Devil's Eye, which switched between an extremely theatrical Hell and the realism of a pastor's household, when the director failed to persuade the cinematographer to soften his lighting techniques. "I felt privileged collaborating with Bergman," Fischer recalled. "He was never indifferent to photography. He could be upset if he didn't like what he saw. Why our collaboration ended with The Devil's Eye, I don't really know. Realistically it's most likely that he thought Sven Nykvist was a better photographer." Thus began the Bergman-Nykvist era, the stylistic change demonstrating how influential the two cinematographers were to the director's oeuvre.

Away from Bergman, Fischer worked on more mainstream movies. For some of these, he was able to use colour, such as The Pleasure Garden (1961), with a screenplay by Bergman, which was among the four films he made with Alf Kjellin. One of the rare films on which Fischer worked for a non-Swedish director was Anthony Asquith's Two Living, One Dead (1961) a low-key film noir, shot entirely in Sweden with a largely British cast (including Patrick McGoohan and Virginia McKenna) but a mostly Swedish crew. Fischer also experimented with video techniques to record a series of provincial circus acts for Jacques Tati's Parade (1974). After his retirement from the cinema in 1975, Fischer lectured on film lighting.

He is survived by his sons, Jens and Peter, who are both cinematographers. His wife, Gull, the sister of the actor Åke Söderblom, died in 2005 after 67 years of marriage.

• Erling Gunnar Fischer, cinematographer, born 18 November 1910; died 11 June 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment