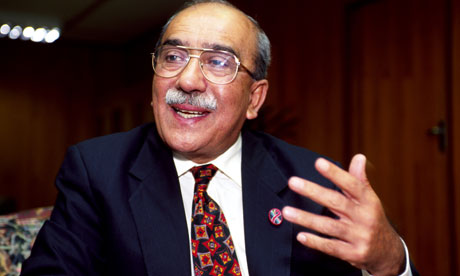

Kader Asmal in 2000. He could be irascible, even withering, but never faltered in his beliefs.

For sheer energy, nobody in South Africa's post-1994, nonracial cabinets could match Kader Asmal, who has died aged 76 following a heart attack. He was not known as "the Bee" for nothing. The first to feel his sting after he was given the relatively junior portfolio of water affairs and forestry in 1994 were his own civil servants, one of whom said, "He terrorised us into activity." But he mixed this with persuasive eloquence, somehow managing to secure the support of Afrikaner civil servants from the old order who, in political defeat, surprisingly saw themselves resurrected as part of a "winning water team".

Kader's dynamism was limitless, and his flair for publicity came to the fore after President Nelson Mandela, to whom he was close both personally and through their African National Congress (ANC) work, appointed him to the cabinet. Envious colleagues complained they could not open a newspaper without seeing Kader turning on a tap delivering clean drinking water to remote rural black communities. Later, he was given some political hot potatoes: chairing the cabinet's conventional arms control committee, concerned with ruling on the ethics of arms sales, the ANC's national disciplinary committee, and parliament's ethics subcommittee.

In the late 1990s, a check-up revealed bone marrow cancer, but it did not slow him down: Kader was not as close to President Thabo Mbeki as he had been to Mandela, yet in 1999 Mbeki advanced him to the more heavyweight ministry of education. With widespread black illiteracy and the legacy of apartheid "Bantu education", some saw this portfolio as another poisoned chalice. Kader reversed or modified some of the over-ambitious policies of his ANC predecessors, introducing the most far-reaching reforms South Africa had ever known. Controversially, he threatened universities with quotas if they did not apply affirmative action to both staff and students.

Kader left government in 2004, and his resignation from parliament in 2008 confirmed his growing disenchantment with the ruling ANC. He left in protest against the disbanding of the elite police unit, the Scorpions, who were investigating an expenses racket among parliamentarians. Kader considered it "immoral" that those involved in "Travelgate" were allowed to vote for the disbanding of the force.

Only last week, Kader repeated his opposition to the Protection of Information bill, widely criticised as being outrageous. Presently before parliament, the bill will give civil servants ranging across state departments the right to prohibit anyone from publishing or commenting on any government document they choose to "classify". Penalties include imprisonment of up to 25 years without the option of a fine.

Journalists, whistleblowers and opposition politicians would be in the front line of this "secrecy bill". Calling on South Africans to reject the bill "in its entirety", Kader said it would destroy trust in the democratic process. The bill was an "appalling measure … deeply flawed".

He also lashed out at Julius Malema, the 30-year-old president of the ANC youth league (ANCYL), described by the opposition Democratic Alliance as a "thugocracy". Malema is engaged in an open bid for power, challenging even the mother ANC. Some analysts think this could result in President Jacob Zuma being ousted at an ANC elective conference in December next year and replaced by someone of Malema's choice. The last ANCYL president, Fikile Mbalula, is being backed by the league for the ANC's secretary-general post. As police minister, Kader said, Mbalula was militarising the police. This was "craziness". If it ever happened, declared Kader, "I hope I won't be alive."

One of seven children of an Indian shopkeeper in Stanger, north-east of Durban, in what is now KwaZulu-Natal – with an impish wit he sometimes called himself "the coolie from Stanger" – he established his reputation as an achiever while still at school, winning Natal's Islamic debating trophy, immersing himself in books and journals, including the New Statesman, and becoming "a lifelong Anglophile", a sympathy that he managed to combine with one for Irish republicanism.

He became a lawyer to equip himself, he said, to fight such atrocities as he had seen in Nazi concentration-camp films. While still in his matriculation year, 1952, he led a student stay-at-home in the ANC's defiance of unjust laws campaign.

A meeting with the ANC president, Albert Luthuli, whose movements were restricted, launched him on his lifelong commitment to the liberation movement. Leaving South Africa in 1959, he went first to London, and then, four years later, to Dublin, to take up a junior lectureship in law at Trinity College. He taught there for 27 years, becoming a senior lecturer, until his return to South Africa after the ANC's unbanning in 1990. Over the course of his career, he gained a teacher's diploma in Natal, a BA by correspondence from the University of South Africa, LLB and LLM from the London School of Economics, MA from Dublin University, and qualified as a barrister at Lincoln's Inn, London; King's Inn, Dublin; and the South African supreme court.

Within months of his arrival in London, Kader launched his protests against what was happening in South Africa with the Boycott Movement; the following year he helped found the British Anti-Apartheid Movement; and in 1963 the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement, which he chaired from 1972 to 1991.

He was also vice-president of the International Defence and Aid Fund for Southern Africa (1966-81), and co-founder and president of the Irish Council for Civil Liberties (1976‑90). Active in support of the feminist movement, he was the only Irish lawyer willing and able to discuss the legal aspects of abortion at a Dublin conference.

In 1979, he served as a member of the International Commission of Inquiry into the Crimes of the Apartheid Regime, and in 1982 was rapporteur of the International Commission of Inquiry into Violations of International Law by Israel. He was also associated with the UN inquiry into the refugee camp massacres at Sabra and Shatila in Lebanon in 1982.

On the ANC's constitutional committee from its founding in 1986, he helped develop a new constitution for South Africa, and returned to his homeland in 1990. He was a member of the ANC's negotiating team for the changeover from apartheid, was elected to its national executive committee, and was professor of human rights law at the University of the Western Cape till 1994, when he was elected to parliament.

Possessed of an insatiable appetite for campaigning, he immersed himself in numerous other South African and foreign committees. In 1995, he was appointed by the World Conservation Union and the World Bank to chair a new body, the World Commission on Dams. He wrote two books and more than 150 articles on apartheid, labour law, Ireland and decolonisation.

Short, bespectacled, a quick thinker and a cricket-lover – as a youngster, he organised a boycott of segregated clubs – he was always affable, chain-smoking through conversations, while reaching for the occasional whisky. Once, when I interviewed him in his ministerial office in Cape Town at 9.30am, he asked me, hopefully, "Bit too early for a snifter, I suppose?"

Kader believed the world could be changed by sheer willpower: he cracked heads, cajoled, pushed, praised. He could be irascible, even withering, but in spite of intermittent asthma, other ailings and a punishing lifestyle, he never faltered in his belief that ideas could be pushed through to conclusions.

His wife, Louise, an Englishwoman whom he had met during his stay in Britain, was an active stabilising force behind the scenes in much of what he did. She survives him, as do their two sons and two grandchildren.

Richard Pine writes: As in South Africa, so too in Ireland, Kader Asmal was a rebel who became a leader. I had the pleasure and privilege of being taught by him at Trinity College in the late 1960s. A provocative lecturer, he would entertain any kind of deviance in classroom debate, if it provided an inroad into the subject we were supposed to be studying – administrative law. I remember his delight when told that the earliest traceable law regarding arrest without warrant dated from the time of Henry VIII, allowing a citizen's arrest if one came upon two clergymen brawling in a churchyard.

Kader was widely admired in Ireland as the founder of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, and it was his evident concern for the underdog – deepened by his knowledge of the Irish experience – that won him public acclaim. I remember him being unsurprised, but deeply disturbed, by the murder in 1982 of his friend Ruth First, author of 117 Days, the account of her detention and interrogation by South African police. It was one of those turning points which oriented him towards his eventual return to South Africa in the pursuit of justice. Irish people continued to follow his career with pride.

• Abdul Kader Asmal, politician, lawyer and academic, born 8 October 1934; died 22 June 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment